April Heaney

I’ll start with a common story for college instructors. Mid-semester passed a few weeks ago, and everyone is feeling the first signs of slump as the days grow shorter. You are beginning to worry (really worry!) about a few students. One of them started the semester as an eager, star-performer but dropped away in the past couple weeks. Another has been coming to class regularly but has turned in almost no work, in spite of several reminders. A third student has had spotty attendance all semester but now is a ghost. Sadly, by the final week of class, one of these students has left campus. In a year, you discover the other two are also no longer enrolled. You are curious and troubled by their decision to leave…but not hopeful that these students will decide to return to school.

Not surprisingly, students leave college in the first year for hundreds of reasons. Some of the most common include financial problems, mental or physical health struggles, family crises, and academic challenges.

For continuing generation students–students whose parent(s) have Bachelors Degrees or higher–a bumpy road to college graduation is often just that—a bumpy road. Leaving college is no picnic, to be sure, but the path back to college is also much more imaginable. To first-generation and underprivileged students, leaving college can feel more like the unfortunate but final ending to a once hopeful story. These students often believe that their departure is evidence that their pervasive fear (ie. I can’t make it in college) is now proven beyond repair.

The deep narrative in our culture about “successful college students” tells us that success looks like four or five years of straight sailing through a major ending in graduation (and a good job). In spite of overwhelming evidence that this story doesn’t hold for many students, we still cling to it in higher education. Our inability to reify any other narratives for our incoming students is harmful in many ways. One of those harms is the complete absence of positive alternate paths in students’ minds. I’ve seen students who are struggling in their first semester continue to dig a deeper hole of poor grades and attendance in their second (and then third) semesters. In the end, they are forced to leave college with a GPA that harms their ability to return, even down the road when they are in better mental and emotional shape to succeed.

This downward path to departure is connected to our single story of college success. When students feel they are slipping, they forge on based on two choices they believe in: keep going or fail at college. To earn poor grades is scary; to depart college even more so—and tied to incredible shame. Institutions do little to help this problem. We fail to build in systematic interventions with struggling students, contact points that can help students see alternate paths to ultimate success in college. We play into the mindset that departure is equated with failing…even when we do communicate to students that leaving is the best option. Financial aid system that does not permit part-time status to keep financial aid. Lastly, we do not widely champion the benefits of a gap-year, especially for students who need that time to understand why they are seeking a college degree.

How Can Teachers Help?

As key contacts for first-year students, teachers have a role to play in altering this harmful mindset. When we see that a student is struggling during a semester, we can change the story we tell them in subtle but meaningful ways. Teachers do need to communicate at the moment when passing the class is impossible—letting students know that withdrawing may be a good choice.

In addition, letting students know that we believe in their potential to succeed in the class (and college) is a huge help to students’ confidence and motivation to succeed. When it seems like a student is struggling across the board in classes, we need to help connect them to a Dean of Students’ contact to review all of their options—not just withdrawing from class, but perhaps withdrawing from school to make it easier to return in the future.

It is important for students to understand that their inability to succeed in college at the present time (e.g. poor attendance, not completing homework, not earning high marks) does not mean they have no hope for the future. A teacher who communicates “I like you/I believe in your potential in spite of your performance this semester/I am in your corner no matter your circumstance at this moment” is a huge encouragement in students’ minds for the future.

On a smaller scale, we can help students understand and act on important dates for course and all-school withdrawal by noting these dates in syllabi and announcing them in class.

Rusin (2018) says, “It’s critical to start thinking of learners who take non-traditional paths to achieving their educational goals as stopouts rather than dropouts. Not only is the term more accurate, but it also has a more positive connotation that influences students, staff and faculty alike.”

In addition to shifting our narrative to struggling students (without changing our academic expectations), we can help bring in stories of successful non-traditional paths to graduating from college. For example, we can tell the stories of students—or colleagues—who needed more time to earn their degree. Normalize the idea of stopping out. A study by Educational Advisory Board (EAB) tracked students at different higher education institution types to see how many returned to college. Hubbard (2020) states, “we were surprised to see that more than half of all students who stopped out would return within a year.” We should know and support this trend.

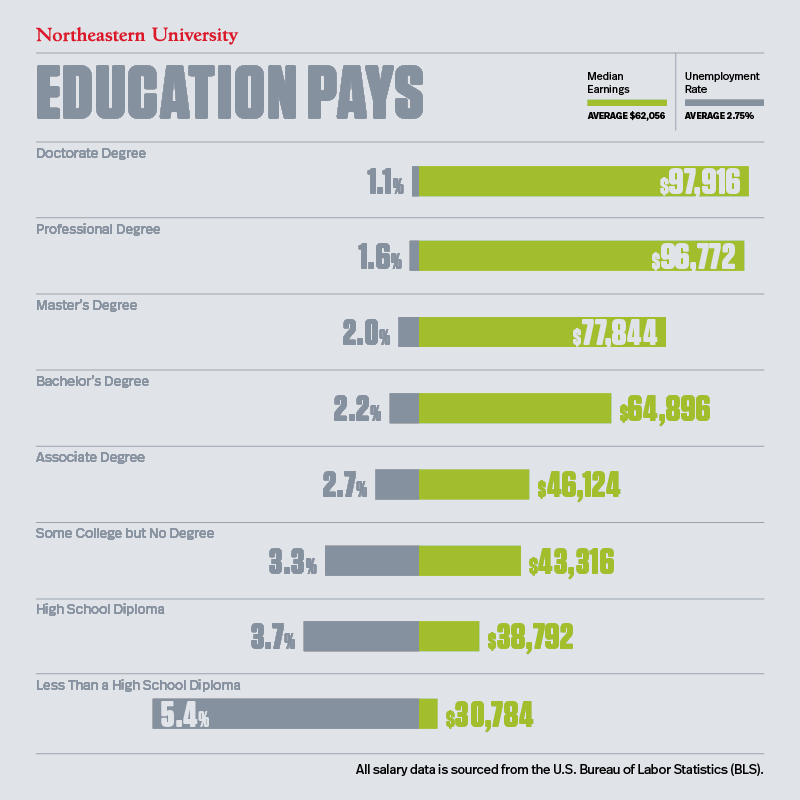

Last Note: I understand (and support!) the irritation some students feel at the constant pressure to equate college degree with successful life/career. There are many, many examples of success stories that are not tied to college degrees. My push in these suggestions is to be more realistic about how to support students who genuinely want a college degree but will struggle to achieve it within a set timeline. In addition, social mobility in the U.S. is tied to college education in ways that further terrible inequities in race and class. The charts below help illustrate why college education matters to this scenario. These outcomes must change.